By Hendre’ Barnard, Training and Marketing Manager

Distillique Beverage (Pty) Ltd.

https://distillique.co.za

Click <Here> to see more of Hendre’s articles.

How do I Dilute my Spirits?

This is one of the most basic steps for any distiller, be it a Home Distiller, Hobby Distiller, Craft Distiller or Commercial Distiller.

Your distillate (or infused product if producing Gin) will come out at a high percentage, and you need to dilute it down to bottling or legal strength.

We do this by adding water.

Sounds simple right?

If only …

How strong should my Distillate be?

Generally, our average distillate strength would vary depending on the product we are producing, and the type of still we are using.

Let’s look at the latter part of that statement first.

If I’m using a Pot Still or Alembic Still, my distillate Alcohol percentage will start high and end low, hence I will have an average strength.

Using Adjustable Reflux Stills or Fractionating Reflux Stills however, I can maintain a constant distillate strength for my entire hearts run.

The product type determines the desired Alcohol percentage based on the amount of flavour I want in the final product, as the higher my alcohol percentage, the lower my flavour profile.

The rule of thumb is that a fruit brandy should be distilled between 60 and 70%, a whisky between 70 and 85%, a vodka above 90% and a neutral spirit above 95%.

This alcohol content must now be reduced to drinkable strength.

It is up to the individual distiller to decide how strong his/her final product should be. Legally in South Africa we have no maximum ABV% (except on Spirit Coolers and a new proposed maximum on Spirit Aperitifs), but we do have a minimum of 43% for most spirit products, with certain types of Brandies having a minimum of 38%.

This only applies to Commercial or Craft Distillers.

A home distiller does not need to keep to Spirit Product Regulations and can make the product at any strength he or she wants to. International ABV% minimums tend to be lower than South Africa’s at 38 to 40% ABV.

The ideal ABV% is one where the “strength” of the spirit, the burning sensation, is not too strong, but the aroma and flavour is clearly detectable.

What Water do I dilute my spirits with?

The Water used for Dilution must be free of hardening substances (specifically Calcium and Magnesium).

These substances are insoluble in an alcohol solution and can cause haziness. Water from primitive rock is usually free of hardening substances and can be used, but as South African groundwater is mostly encased in Dolomite, we tend to have much harder water with high mineral concentrations.

Excessive minerals can cause haziness in the diluted product, or even sedimentation if the product is chilled or left too stand. It is especially observable in wooded or barrel aged products where the minerals bind with colour compounds.

As a rule of thumb, water containing up to 89.4 ppm (parts per million) of Calcium Carbonate and Magnesium is still acceptable – more than that becomes risky.

In addition, it is important for the water to be flavour neutral, hence any water treated with Chlorine or Fluoride is not ideal.

If your local water source is not suitable as is (and it normally is not) you have a couple of options:

- Reverse Osmosis Water Filtration – Home units are suitable for the Home Distiller, but the Commercial Distiller or Craft Distiller will need an Industrial unit – 100 lt per hour or more – to produce properly filtered water in large enough quantities for dilution purposes.

- Distillation of Local Water in your still – suitable for the Home Distiller, but not commercially viable for the Commercial Distiller

- Treating Water with Water Softener – suitable for the Home Distiller, but not advisable for Commercial or Craft Distillers, due to the continuous expense and chemical addition

- Purchasing Distilled / RO Water – sold at most Pharmacies, this would only be a solution for the Home Distiller

NOTES:

- When using a RO Filter, it is better to filter a large quantity at a time, than filtering a little bit every day – this will increase the life expectancy of your equipment

- If filtering larger quantities of RO Water, please ensure you use it within a 5-day period as it can start smelling and tasting musty if it stands too long

- If water quality is really a problem, with lots of Chlorine, Metals and/or Minerals in the water source, pre-filters should be used to treat the water prior to using it in Fermentations, and before sending it to the RO Filter. This will extend the life expectancy of the Filter Material and RO Membranes. Pre-filters can include UV Treatment (for bacteria), Water Softener (for minerals), a Deionizer (for metals like copper and zinc), a Dechlorinator (for excess chlorine) and a Sand Filter (for particulates).

- Rainwater is ideal to use, as long as the Catchment system is clean. It is not however feasible for Commercial or Craft Distillers as consistent supply cannot be guaranteed and changing dilution water sources is introducing a variable into the production process.

- Some distillers feel that water with a little bit of mineral salts tastes better and makes for a better tasting product. Remineralization pack can be used to add the correct dosage of minerals too RO water to achieve this.

How much Water do I add to dilute?

For a Home Distiller or Hobby Distiller the method of calculating Water to Add during Dilution is relatively straight forward.

V x MALC% = AA

Volume x Measured Alcohol Percentage = Absolute Alcohol

AA / RALC% = TV

Absolute Alcohol / Required Alcohol Percentage = Total Volume

TV – V = WTA

Total Volume – Volume = Water to Add

NOTE: This formula is not Volumetric Scale specific, so you can use litres or millilitres and the formulas will still work. Just keep it constant – you cannot chop and change between scales. It is however Metric Scale specific.

Also note that the percentages must be used in DECIMAL form, i.e. 60% is 0.6 and 74% is 0.74

EXAMPLE: To dilute 2 400 millilitres of 66% alcohol down to 43%.

V x MALC% = AA

2 400 x 0.66 = 1 584

AA / RALC% = TV

1 584 / 0.43 = 3 683.72

TV – V = WTA

3 683.72 – 2 400 = 1 283.72

So, I need to add 1 283.72 ml of water.

This method is known as Approximate Quantitative Determination through Calculation, and it is completely suitable for the Home or Hobby Distiller, but not for the Commercial or Craft Distiller.

The reason is that calculating the necessary quantity of water to add is not as simple as indicated, due to the fact that mixing alcohol and water causes a volume reduction (known as Contraction).

What is Contraction?

When 50 millilitres of water is added to 50 millilitres of alcohol, the volume of the two mixed together will be expected to be 100 millilitres.

When you measure it however, it will only be about 96 or 97 millilitres.

When water and ethanol is mixed together, the combined molecules fit together better than when they are pure, so they take up less space.

The reason is that the sizes of the individual molecules are different enough that the smaller molecules can slip into the spaces between the big molecules.

More specifically, if you want to get into the chemistry of things, the reason that the volume is less is due to molecular bonding – specifically, the creation of Hydrogen bonds.

The OH- component of alcohol interacts with the H+ of the water molecules.

These bonds attract each other to the point of making “hydrogen bonds”, and these hydrogen bonds result in a tighter molecular formation, thereby reducing the overall volume of the combined liquids.

This water and ethanol mix is called a solution.

Now, the process of solution formation is exothermic, and a substantial amount of heat energy is released.

This becomes quite important later.

So, in practice, because of volume reduction or contraction, a distiller will need to use MORE water than calculated in order to get the correct Alcohol by Volume percentage.

A simple way to achieve more accurate dilution is be adding the calculated quantity of water, measure the alcohol content of the solution, and then correcting it by adding small amounts of water.

Doing this, however, requires PRECISE Measurement of the Alcohol Percentage (see below).

Can I allow for Contraction in my Dilution Calculation?

A more accurate method of doing Dilution is through the use of a Mixture Table.

Using the Mixture Table, the Distiller can determine the exact amount of water to be added, as the volume contraction (volume reduction) is already factored into the amount given on the table.

The Distillique Mixing Table for High Percentage Distillates provides calculations based on 100 litres of Distillate – allowing the user to search down the left hand column for the measured Alcohol Percentage at 20° Celsius for the 100 lt of Distillate, then search along the row to the left for the column of the ABV% he/she is aiming to dilute too, and the indicated figure in the Cell will be the amount of water to add to the 100 lt of Distillate in litre.

The formula used to calculate the volume of water to add for quantities smaller than 100 litres is:

V x WTAFT / 100 = WTA

Volume x Water To Add From Table / 100 = WTA

Please note that now, the Volume must be in litres.

If we use the same example as before: Dilute 2 400 millilitres of 66% alcohol down to 43%.

V x WTAFT / 100 = WTA

2.4 x 55.4 / 100 = 1.385

The corrected amount of water to add is therefore 1 385 ml, opposed to the basic calculated amount of 1 283.72 ml. A difference of almost 102 ml.

But again, this only works if we have precise and accurate measurements for the Alcohol Percentage.

How do I measure my Alcohol Percentage accurately?

Three factors play a role in accurate Alcohol Percentage Measurements – Scale, Parallax and Temperature.

Before we get to that though – what is an Alcoholmeter, or more accurately, an Alcohol Hydrometer?

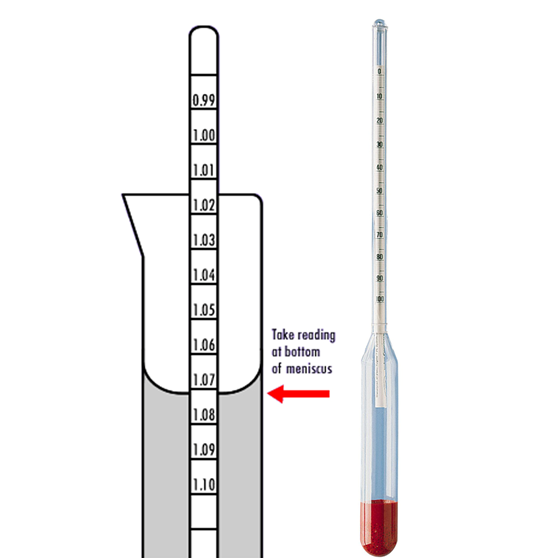

A hydrometer is an instrument used to measure the specific gravity (or relative density) of liquids; that is, the ratio of the density of the liquid to the density of water.

A hydrometer is usually made of glass and consists of a cylindrical stem and a bulb weighted with mercury or lead shot to make it float upright. The liquid to be tested is poured into a tall container, often a graduated cylinder, or specially designed hydrometer cylinder, and the hydrometer is gently lowered into the liquid until it floats freely.

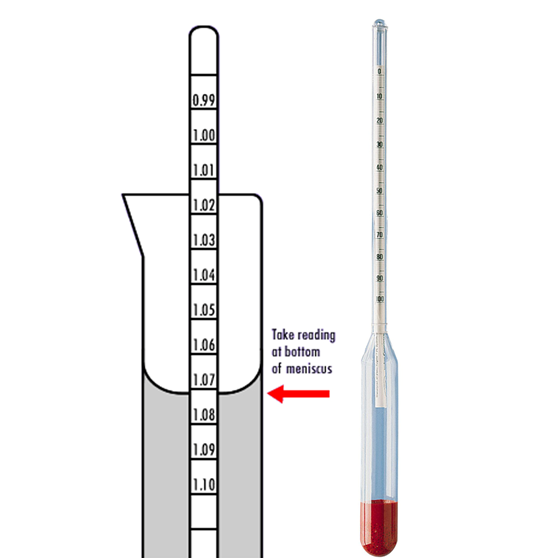

The point at which the surface of the liquid touches the stem of the hydrometer is noted.

Hydrometers usually contain a scale inside the stem, so that the specific gravity can be read directly.

Put an SG Hydrometer (used to measure Sugar Content – more accurately dissolved solids) and an Alcoholmeter, works in this manner.

Clear? Right.

First – let us look at Scale.

The standard alcohol meter used by Home or Hobby Distillers is the 0 to 100% ABV Alcohol Meter. The stem with the measurements from 0 to 100% is approximately 10 centimetres long, and graduated in 1% increments – but at the top the increments are every 2 mm, while at the bottom it is less than a millimetre apart, hence the lower the percentage you measure, the less accurate it becomes.

The Laboratory Grade Professional alcohol meters on the other hand, has a stem almost 12 centimetres long, also graduated in 1% increments, but now the spacing between increments remains constant, and because each Lab Grade alcohol meter on measures 10% (40 to 50, 50 to 60, etc.) each percent occupies almost more than 1 centimetre, making for MUCH more accurate readings.

Secondly, the Parallax Error.

Think back now to High School Chemistry.

The Parallax error is a measurement error caused by the fact that the apparent position of the hydrometer differs from the actual position due to the viewing angle not being perpendicular to the hydrometer.

In other words, if you try to read the hydrometer at an angle through the liquid, the liquid “bends” the light refracting through it, and you get the wrong reading.

You need to make sure your eyes are level with the liquid in order to get the right reading.

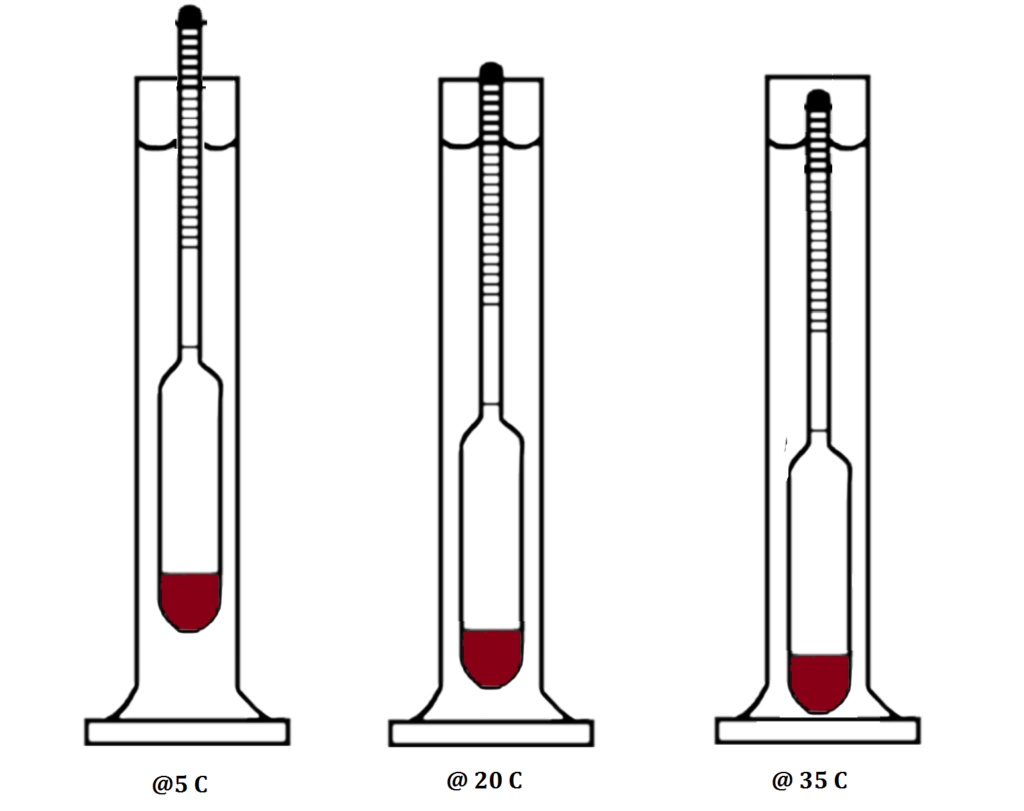

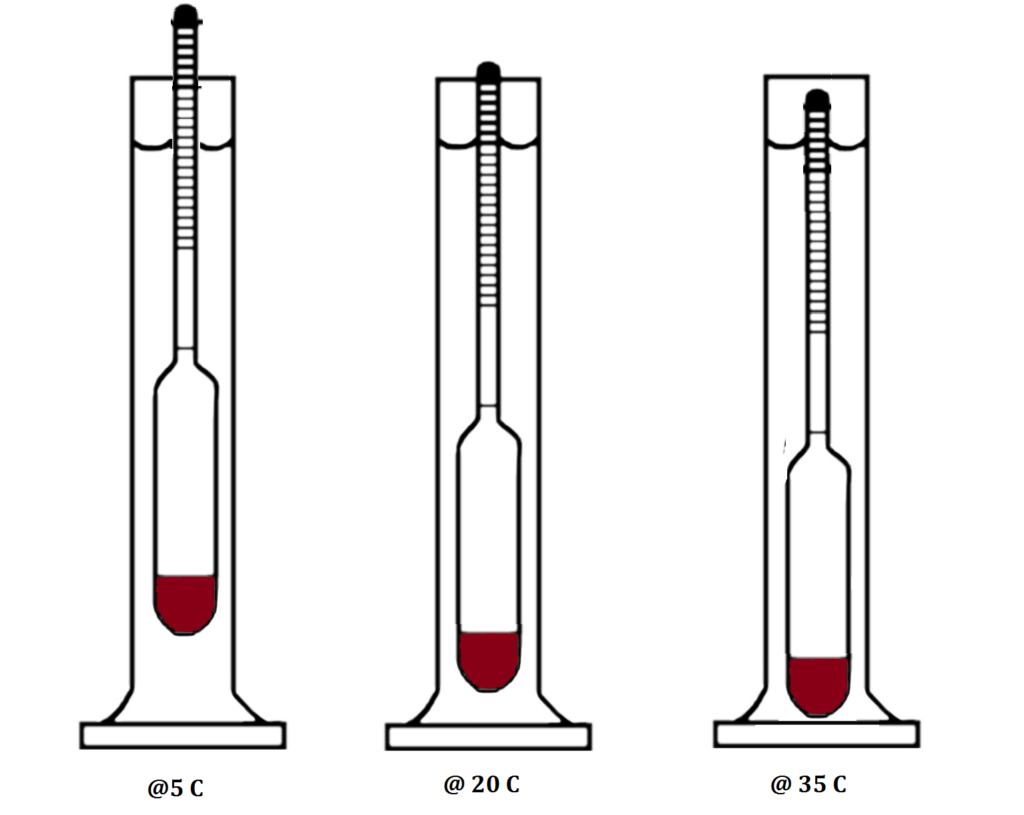

Lastly, the Temperature of the Distillate or Solution.

An Alcohol meter is generally calibrated to 20°C, meaning that when you measure your spirit it should be at 20°C. If your spirit is above 20°C it will be less dense (lighter) then at 20°C and the hydrometer will sink lower, giving you an artificially high reading. If on the other hand your spirit is at a temperature below 20°C, the liquid will become more dense and float higher, giving a lower reading.

Now, cooling or heating alcohol to get the right temperature in order to get the right readings can be a pain, so we don’t do that. We use an Alcohol Meter Temperature Correction Table to adjust our reading at the “incorrect temperature” to the reading at the “correct” temperature.

As stated earlier, this is normally at 20° Celsius, but it may sometimes be 15° Celsius.

It is also important to remember that the spirit you are measuring, and dilution should not contain any additives such as glucose, flavourings or vegetable glycerine, as any foreign substance will affect the density of the liquid, and therefore affect your reading.

How do I use a Temperature Correction Table?

Draw a sample of your distillate, and using a Lab Grade Alcoholmeter, measure the ABV%. Write it down. At the same time, using an accurate digital thermometer, measure the current liquid temperature of the distillate.

Now get your Temperature Correction Table.

Step 1: At the top of the table in the first row you’ll see numbers. This represents the temperature of the spirit. Search along the top row till you find the current temperature of your distillate as measure.

Step 2: What was your measured ABV Percentage? Search down the column of the temperature you measured until you find the closest reading to our measurement.

Step 3: Now, from that closest reading, follow the row to the left until you come to the 20° Column, or the first column (in peach) – both values should be the same, and it will give you the actual and corrected ABV% for your measurement at the measured temperature.

That corrected ABV% is the figure you use in your calculations.

What if I don’t have my Temperature Correction Table?

To estimate the actual ABV% without a temperature correction table you just need to remember one general rule:

For every degree Celsius you are over 20° Celsius, subtract 0.33% from your hydrometer reading.

In other words, if the Actual Temperature of spirit is 30° Celsius, and your Alcoholmeter reading is 93% ABV, the actual ABV% can be calculated in the following manner:

Actual ABV% = 93% – (0.33 x (30 – 20))

Actual ABV% = 93% – (0.33 x 10)

Actual ABV% = 90.7%

If you’re not a fan of the Correction Tables, and the Estimation Technique is a little crude for your liking, there are many free Alcohol Hydrometer Temperature Correction Calculators available online.

How do I add Water to my Distillate?

If Water is added incorrectly, even if it is the right water, you could still experience cloudiness or hazing.

Always remember the following:

- The water and the distillate should be at the same temperature when mixed. This can be achieved by allowing both to sit in similar tanks for a day or two prior to dilution.

- The water is always poured into the distillate and never the distillate into the water.

- The water should be poured into the distillate in a fine stream while stirring constantly.

Water and distillate mixes slowly, so if water is added too quickly, and alcohol under-concentration can occur where the water contract the distillate, and this can result in haziness.

If you have reason to believe that you have large(r) concentrations of oils in your distillate, either it is a Brandy type product, a Gin or something like Ouzo, you should dilute in stages – 10% every 2 to 3 days. This will cause these compounds to form or congeal in larger particulates that can be filtered out without chilled filtration which could lead to loss of flavour.

In some cases, you might experience cloudiness or hazing as the ABV% gets lower.

This is especially true with the products mentioned earlier – Brandy, Gin and Ouzo – and it happens because the solvency of the ethanol is reduced as you reduce the ABV%, meaning oils that are kept in suspension, drops out of suspension.

To remove this cloudiness or haze you will need to apply chilled filtration – cooling the diluted spirit below 0 degrees Celsius, allowing the oils to congeal, and then filter through paper plates which will absorb and therefore remove the oils.

Unfortunately, chilled filtration removes not only haze, but flavour as well.

A better option is to dilute the spirit not to the minimum legal required level, but the minimum level where the oils still stay in suspension.

Why do I get Haze during Dilution?

If you read this article carefully, you would know we have two possible causes for haze – either you have minerals in your water, or you have oils in your distillate.

How do I know which is which?

Easiest way to find out is to put a sample of your Hazy Dilution in the fridge – normally overnight is long enough if the fridge is cold enough. If the haze is caused by mineral salts, you should see sediment at the bottom. If it is because of oils, you should see a layer of oil form (normally at the top).

Anything else?

Yes.

If you read carefully and have a good memory, you would recall that earlier I mentioned that the process of solution formation is exothermic, and that a substantial amount of heat energy is released.

This means that when you dilute – especially high percentage distillates – or if you dilute too fast, the solution will get hot. This can also cause unwanted flavours to form, and if you are taking readings at that time, your readings will be affected as well.

Hopefully this article will answer all the questions you might have regarding Spirit Dilution.

Incorrect Readings – Comparing Refractometer and SG Hydrometer Readings

From time to time Clients contact us with a question relating to the different readings obtained when using both a Refractometer and a floating SG Hydrometer in the same liquid.

These readings can be quite far apart and we should be aware of that and the reasons behind it.

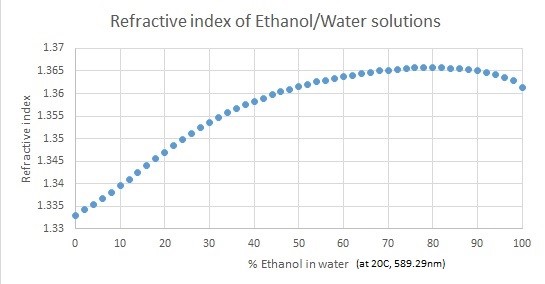

The general “truth” that more dense liquids have greater Refractive Indexes (i.e. sugar water vs water), and less dense liquids (i.e. ethanol vs water) have smaller Refractive Indexes is not true.

Snell’s law states that the refractive index for more optically dense liquids will be bigger and that less optically dense liquids will have smaller refractive indexes.

The key here lies in the fact that optical density does not necessarily correlate to the physical density of a material.

In summary, if you use a Refractometer to measure the Brix value in fermenting mashes, be aware that the produced alcohol will cause the Brix Refractometer to indicate inflated readings, i.e. showing a 6% Brix reading when it actually should be 0% at the end of the fermentation).

Also, if you use a SG Hydrometer to measure the Brix value in fermenting mashes, be aware that the produced alcohol will cause the Brix hydrometer to indicate readings that are lower than actual, i.e. reading -3% Brix when it should actually be 0% at the end of the fermentation.

Below is a summarizing comparison between the two Instruments:

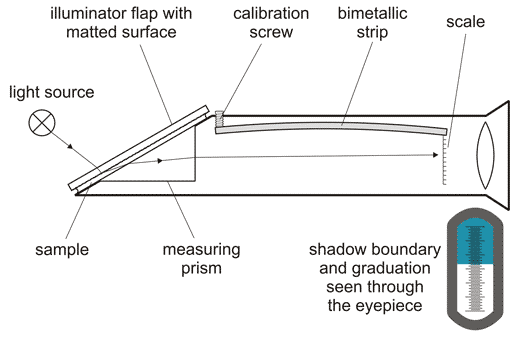

What is a Refractometer?

A refractometer is a simple instrument used for measuring concentrations of aqueous solutions.

When light enters a liquid it changes direction; this is called refraction. Refractometers measure the degree to which the light changes direction, called the angle of refraction. A refractometer takes the refraction angles and correlates them to refractive index (nD) values that have been established. Using these values, you can determine the concentrations of solutions. For example, solutions have different refractive indexes depending on their concentration in water.

A Refractometer measures the Optical Density of a Solution, and depending on what it is scaled for – sugar or ethanol – it will give you an accurate SG and Brix Reading (if scaled for Sugar) or an accurate %ABV or Proof Reading (if scaled for Alcohol). Refractometers are mostly calibrated for 20 degrees Celsius and are most accurate if the liquid being measured is at that temperature. Most Refractometers are also equipped with ATC functionality – Automatic Temperature Correction – which can adapt to small variances in temperature.

When measuring sugar values in a solution containing sugar, water AND ethanol – in other words, when using a Refractometer to track a Fermentation, it will give too high sugar readings, i.e. the Brix values will be higher than actual sugar content.

What is a Hydrometer?

A hydrometer is an instrument used for measuring the relative density of liquids based on the concept of buoyancy, or direct density. They are typically calibrated and graduated with one or more scales, for instance, most SG Hydrometers (used to measure sugar content) is called Triple Scale SG Hydrometers, meaning they can measure SG Scale (mostly used by Brewers), Brix Scale (the new international standard, and very close to the old Balling Scale) and Approximate Alcohol Potential Scale (an indication of the percentage Alcohol By Volume – ABV – that will be produced during fermentation with the measured sugar concentration). Alcohol Hydrometers, or just Alcoholmeters, are normally calibrated in %ABV, Proof, or both.

Hydrometers – both SG and Alcohol – are calibrated to a desired temperature, mostly 20 degrees Celsius, but sometimes 15 degrees Celsius. This is true for Refractometers as well, but unlike Refractometers, the Hydrometer cannot self-calibrate or adjust, even for small variances. The warmer a liquid or solution is, the less dense it is, the deeper the Hydrometer will float, hence with a Sugar Hydrometer you will get a lower reading in a fermentation sample, and in distillate with an Alcoholmeter you will get a higher reading. Inversely, if the liquid or solution is colder than the calibrated temperature, the SG Hydrometer will read a higher sugar level in the Fermentation, and the Alcoholmeter a lower alcohol percentage in the distillate.

Another aspect to consider is where you are taking your reading.

Through surface adhesion, a liquid forms a meniscus between itself and the surface of both the measuring cylinder and the stem of the Hydrometer. Readings should be taken inline with the bottom of the meniscus, at eye level, and not at an angle which will give incorrect readings (known as the Parallax Error.

A Hydrometer measures the Direct Density of a Solution, and depending on what it is scaled for – sugar or ethanol – it will give you an accurate SG and Brix Reading (if scaled for Sugar) or an accurate %ABV or Proof Reading (if scaled for Alcohol).

When measuring sugar values in a solution containing sugar, water AND ethanol – in other words, when using a Hydrometer to track a Fermentation, it will give too low sugar readings, i.e. the Brix or SG values will be lower than actual sugar content.

HOWEVER, The SG Hydrometer is much less affected by this than a Refractometer, therefore it is still more than accurate enough to track fermentation progress, and it is still the preferred choice for this activity.

More Information on Refractometer Readings

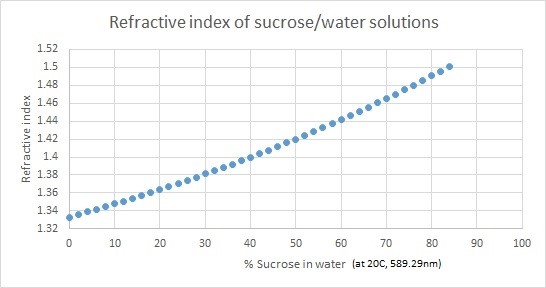

The following graphs displays the refractive indexes of ethanol/water and sucrose/water solutions.