By Hendre’ Barnard, Training and Marketing Manager

Distillique Beverage (Pty) Ltd.

https://distillique.co.za

Published : 26-02-2020

Different ways in which Still Shape Impacts Spirit Quality

Both the still shape and size have a significant effect on the character of the spirit being produced – and it has a lot to do with copper.

In a previous article we explored the use of Copper in stills, specifically comparing it to the use of Stainless Steel, the removal of Sulphur Compounds, and whether or not the use of Copper Stills could lead to cancer.

As was mentioned in that article, and in our training courses, Copper was first used to make stills because it is malleable and can be worked into shape easily, but it’s long been realised that it also has its own properties that are a significant aid to distillers.

It is in considering these attributes that the shape of the still comes into play. Most noticeable in the vapour chambers of alembic or pot stills.

It is all to do with something that Master Distiller Mike Nicolson (previously with Diageo, and more recently with Shelter Point) calls the ‘conversation’ between Copper and Vapour.

Where does the process start?

Let’s go back one step in the process. The fermentation (be it beer, wine or a sugar wash) made in the fermentation vessels is a complex mixture of water, ethanol, and then most importantly, different flavour compounds known collectively as congeners.

What distillation does, is to concentrate these compounds and congeners – depending on the way you look at it, “purifying” them – and then allowing the distiller to selectively choose and collect the specific flavours he or she wishes to have in the final product. Collegially this is known as making cuts.

Now, some of these compounds – sulphur, for example – are categorised as being ‘heavy’.

NOTE: Referring to these compounds as ‘heavy’ can be misleading, as some people assume that when we refer to a ‘heavy’ compound, we are talking about actual, physical mass. This is not the case. The molecular weight of Ethanol is 47.06 g/mol, while the molecular weight of Hydrogen Sulfide (one of the unwanted congeners) is only 34.1 g/mol. The usage of the term in this context actually refers to the flavour profile and not the mass.

These ‘heavy’ compounds, also tend to be compounds which copper can remove from the vapours during the distillation process.,

This is where the Copper vs Vapour conversation begins.

Copper as a Psychiatrist

Mike Nicholson uses the metaphor of the Fermentation being a severely troubled individual, dealing with all kinds of problems, baggage and the like. It is being weighed down by methanol, acetone, hydrogen sulphide and a host of other unwanted ‘issues’.

The Copper acts as a Psychiatrist, wanting to help the fermentation ‘unburden’ itself by getting rid of all this baggage.

The fermentation is brought to a boil, and the vapours carry the compounds up to the copper – the start of the conversation.

The longer the conversation is between vapour and copper, the lighter the spirit will be, the more unburdened. The longer the vapours talks to the copper, the more it unburdens itself, the lighter it becomes.

So, the more copper contact, then more sulphur (and other ‘heavy’ compounds) are removed.

So, how does the Vapour Chamber (hood) Shape play a role in this?

Now, enter shape.

You can hopefully see why it is logical to assume that a tall still will be more likely to make a light spirit. Conversely, a smaller still (shorter still) is more likely to make a heavy spirit because that conversation is a short one.

There are various ways in which you can further extend (or shorten) that conversation. Putting a small amount of spirit in the still makes more copper available (assuming a copper boiler), while running the still slowly also prolongs the potential conversation.

There is another element at work: the process known as reflux. This happens when some of the vapour meets a cooler surface inside the still, turns back into liquid, falls back down the still and is re-distilled. The more reflux there is, the lighter and more complex the spirit will be.

Again, shape plays a role.

A tall still will have lots of reflux, as will stills that have packing or boil bulbs at the base of the neck. Boil bulbs are dents or protrusions found in the vapor path which increases the internal surface area of the vapour path, thereby increasing the reflux.

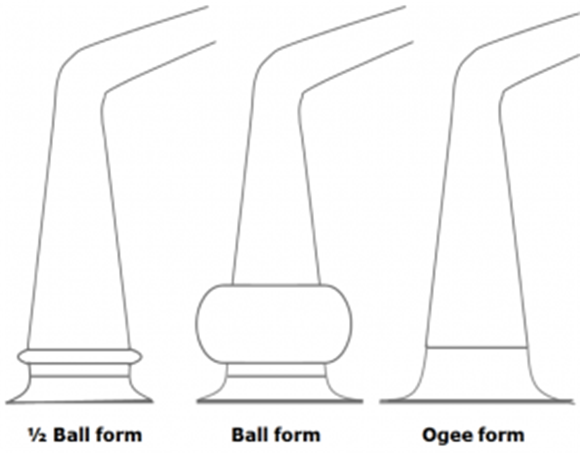

‘Mushroom Shaped’, Ball Form, 1/2 Ball Form, Moorish or Onion Dome Stills, which have a narrow waist and then flare out, will also promote reflux.

Considering the Lyne Arm

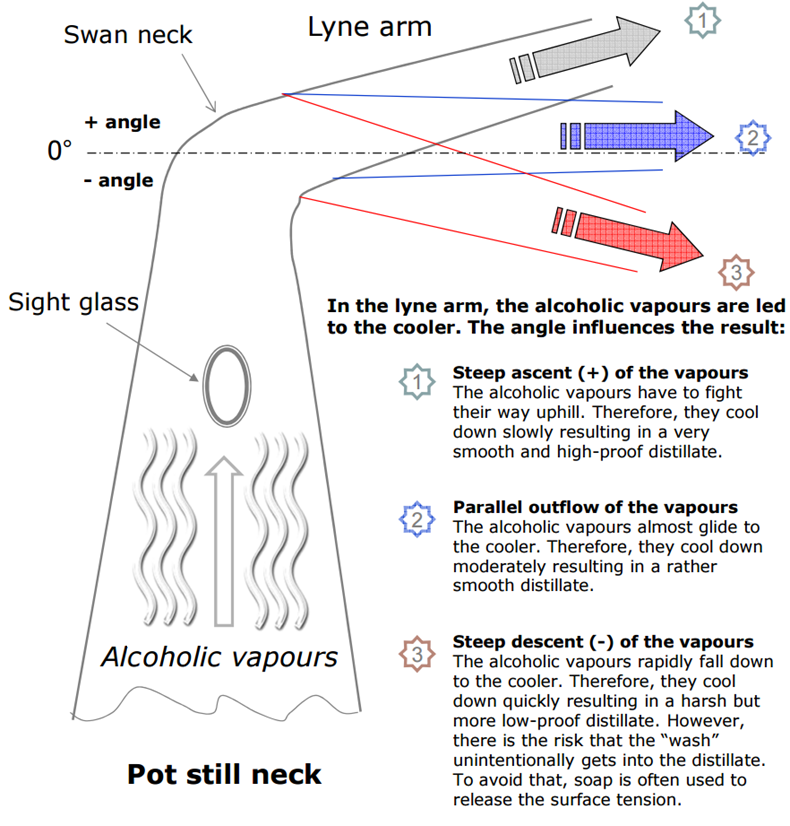

The angle of the Swan’s Neck or Lyne Arm also has an impact.

The Swan’s Neck is the curved section of copper tube that connects the Vapor Chamber on top of the boiler, to the Condenser. The Lyne Arm in its simplest form is basically the same – a cylindrical copper tube that connects the Vapor Chamber on top of the boiler, to the Condenser. The difference is however that the Lyne Arm is almost never curved. As it leaves the Vapor Chamber, it can either:

- angle upwards

- run horizontal

- angle downwards

But almost always in a straight line.

If the Lyne Arm or Swans Neck points upwards, the Copper conversation (if constructed out of copper or containing copper mesh/packing) and reflux is further extended.

However, if the Lyne Arm or Swans Neck angles downwards, this stops the conversation in its tracks. Doing this will cause the vapour retain more congeners, and helps the distillate to gather more and deeper flavours.

Condensers also have their part to play in this, and we will address this in another article.

Do we want to remove all Heavy compounds?

It’s important to understand though that ‘heavy’ is not necessarily bad.

Distillers choose the shape of the still and manage the way it is run in order to produce the specific congeners that create the distillery’s unique character.

A heavy, sulphury spirit – sometimes described as ‘Meaty’ is desirable in many cases.

Now, you may have noticed that I’ve not said tall stills automatically make light spirit. Distillers can run the stills in the opposite way to which they were originally intended. Very small stills, for instance, should mean a short conversation and a heavy spirit, but if the stills are not filled to capacity, leaving more space in the boiler, and the distillation is slow, this will result in a light spirit – albeit one with some heavier characteristics.

Conversely, a tall still can be run in a way which deliberately exhausts the copper. Result? A heavy spirit, but this time it will be one with extra complexity because there’s still reflux going on, just without the extra influence of copper.

The shape does still play a part, but it also comes down to the skill, decisions, control and methodology of the Distiller – the Craft.

So what type of Still should I choose?

Particular distilleries swear by the size and design of the respective stills they use.

Roughly, we can say that small stills create a more aromatic distillate than large ones and that stills with a long neck create a smoother distillate than those with a short neck.

Additionally, there are different designs for the neck of a pot still, which have a considerable impact on flavour and characteristics of a distillate (see above).

And finally, the design and angle of the lyne arm more or less determines the quality and intenseness of each distillate.

All of this is just different ways of affecting the same process – reflux.

In the end, if you have a still with Variable Reflux – either an Adjustable Reflux Column Still or a Fractionating Reflux Column Still, you have to opportunity to play with the reflux (and in a modular design, with the amount of copper contact), until you find a configuration and mode of operation that you desire, and creates the product and flavour profile you want.